What this post aims to

do is examine the ways in which the nations are impacted by the chronicity of

the wars they’ve endured as well as the coping mechanisms that they employ to bear

these hardships. Aside from the predictability of physical pain and illness,

there is a disturbing sense of normalization and domesticity in how the nations

negotiate their lifestyles in war. It’s

maladaptive.

That said, let’s go over

some examples.

Physical Pain and Illness:

The most obvious impact

of war and political struggles—both

domestic and international—is the physical strain that it puts on a nation’s body.

Ex: During the Second World War, Germany and Italy are both taken as

prisoners of war. Germany compares the pain of torture to a mosquito bite, as

his daily life is far more painful.

Ex: England falls ill on several occasions following major political conflicts

(e.g., the American Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, World War II) [x].

Ex: China complains of body aches, stemming from political infighting

in his country [x] [x].

Sense of Helplessness:

Of course, smaller

powers are rendered vulnerable and pliable to the discretion of larger powers.

Ex: Belgium and Luxembourg discuss their inability to protect themselves

during both World Wars [x].

Ex: The conditions that Russian soldiers experienced were so bad that

Russia becomes ecstatic when Germany takes him as a prisoner of war. He

compares the German POW camps to heaven.

Ex: England’s normalized being captured by

the Axis and pre-preemptively brought a spare change of clothes [x].

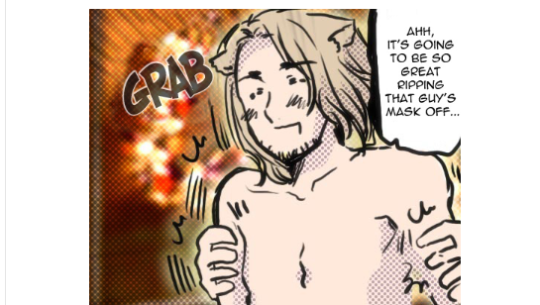

Suspicion and Hostility:

War is a breeding ground

for distrust and betrayal. As such, the nations must always be ready to fight

for their lives, even in seemingly innocuous circumstances.

Ex: When the two first

meet in World War I, Germany second guesses himself several times on whether

Italy poses a threat to him.

Ex: Russia shares his tea

ration with England. While skeptical at first, England accepts. The sweetness

of the tea initially causes England to conclude that Russia poisoned him. What

matters here is the fact that England rationalized this outcome as a legitimate

possibility…[x].

Domesticity, Normalization, and Adaptation:

As horrible and gruesome

as war may be, there are still moments where the nations are able to enjoy

themselves and share a good laugh. The problem, then, is that having had

experienced countless wars, the nations bring the domestic into the world of

war—i.e., war becomes their home and the private

and public sphere divide becomes muddled.

Ex: England drinks tea in

the middle of the battlefield. Trivial as this may appear, on a latent level,

he’s attempting to include a routine and sense of normalcy in an environment

that is otherwise chaotic and unpredictable.

Ex: After infiltrating

America’s war camp, Prussia teases Germany for his impression of an American.

Ex:Having just occupied

Rome, America asks the terrified Italy Brothers if they could make him

authentic Italian cuisine [x].

The casualness in the way

America speaks is disturbing considering that from his perspective, taking over

another country is normal. It’s not

something that should produce fear but rather should be accepted as is. He

doesn’t consider the Italy Brothers to be his personal enemies. The personal is not political in this case.

Relief:

The best nations that

illustrate the burdens of war are those who have passed on. Rome and Germania

visit Earth together and upon reflecting on their lives, they reach a similar

conclusion: death gave them a sense of liberation.

They’re no

longer bound by their bosses’ orders and aren’t forced to participate in wars

they have no interest in being involved in [x].